It's Garry I Wanna Hit You to the Beat Its Garry Baby

| Gary Moore | |

|---|---|

Moore performing at Pite-Havsbad beach, Piteå, Sweden, in 2008 | |

| Groundwork information | |

| Nativity proper noun | Robert William Gary Moore |

| Born | (1952-04-04)4 April 1952 Belfast, Northern Republic of ireland |

| Died | 6 February 2011(2011-02-06) (aged 58) Estepona, Spain |

| Genres |

|

| Occupation(s) | Musician, songwriter |

| Instruments | Guitar, vocals, bass, keyboards |

| Years active | 1968–2011 |

| Labels | MCA, Jet, Virgin, Sanctuary, Hawkeye |

| Associated acts | Skid Row, Thin Lizzy, Colosseum II, Yard-Force, Greg Lake, BBM, Scars |

| Website | gary-moore |

Robert William Gary Moore (4 April 1952 – half dozen Feb 2011) was a Northern Irish musician, singer and songwriter. Over the course of his career he played in various groups and performed an eclectic range of music including blues, hard rock, heavy metal, and jazz fusion.

Influenced by Peter Green and Eric Clapton, Moore began his career in the late 1960s when he joined Skid Row, with whom he released ii albums. After Moore left the grouping he joined Thin Lizzy, featuring his former Slip Row bandmate and frequent collaborator Phil Lynott. Moore began his solo career in the 1970s and achieved major success with 1978's "Parisienne Walkways", which is considered his signature song. During the 1980s, Moore transitioned into playing hard rock and heavy metal with varying degrees of international success. In 1990, he returned to his roots with Still Got the Blues, which became the most successful album of his career. Moore continued to release new music throughout his after career, collaborating with other artists from time to fourth dimension. Moore died on 6 February 2011 from a centre attack while on vacation in Spain.

Moore was oftentimes described every bit a virtuoso and has been cited equally an influence by many other guitar players. He was voted as ane of the greatest guitarists of all time on respective lists by Total Guitar and Louder. Irish singer-songwriter Bob Geldof said that "without question, [Moore] was 1 of the great Irish gaelic bluesmen".[one] For most of his career, Moore was heavily associated with Peter Green's famed 1959 Gibson Les Paul guitar. Later he was honoured by Gibson and Fender with several signature model guitars.

Early life [edit]

Robert William Gary Moore was born in Belfast on 4 April 1952,[ii] [three] the son of Winnie, a housewife, and Robert Moore, a promoter who ran the Queen's Hall ballroom in Holywood.[2] [3] [four] He grew upward near Belfast'southward Stormont Estate with four siblings.[iii] He credited his male parent for getting him started in music. When Moore was half dozen years old, his father invited him onstage to sing "Sugartime" with a showband at an consequence he had organised, which kickoff sparked his interest in music. His begetter bought him his first guitar, a second-hand Framus acoustic, when Moore was 10 years old.[three] [5] [6] Though left-handed, he learned to play the instrument correct-handed.[v] Not long subsequently, he formed his starting time band, The Beat Boys, who mainly performed Beatles songs.[iii] [five] He later joined Platform Three and The Method, amongst others.[7] Around this time, he befriended guitarist Rory Gallagher, who often performed at the aforementioned venues as him.[8] He left Belfast for Dublin in 1968 just as The Troubles were starting in Northern Ireland. A year later on, his parents separated.[ii] [iv]

Career [edit]

Skid Row [edit]

After moving to Dublin, Moore joined Irish dejection rock band Skid Row. At the time, the group were fronted by vocalist Phil Lynott. He and Moore soon became friends, and they shared a bedsit in Ballsbridge.[two] Yet, later on a medical leave of absence, Lynott was asked to leave Slip Row by the ring'southward bassist Brush Shiels, who had taken over lead vocal duties.[9] [10] In 1970, Skid Row signed a recording contract with CBS,[eleven] and released their debut album Sideslip, which reached number 30 on the UK Albums Nautical chart.[12] Later on the album 34 Hours in 1971, and tours supporting The Allman Brothers Band and Mountain amid others, Moore decided to leave the band.[eleven] [thirteen] Moore had become frustrated by Sideslip Row's "limitations", opting to start a solo career.[3] In retrospect, Moore stated: "Skid Row was a laugh just I don't have actually fond memories of it, because at the time I was very mixed upward about what I was doing."[xiv] In 1987, Moore was asked to sell the rights to the name "Slip Row" to the American heavy metal ring of the same proper name, which he eventually did for $35,000.[15]

Thin Lizzy [edit]

Moore (right) with Thin Lizzy in early 1974.

Afterward leaving Skid Row, Phil Lynott formed the hard rock group Thin Lizzy. After the difference of guitarist Eric Bell, Moore was recruited to assistance stop the band's ongoing bout in early 1974. During his time with the group, Moore recorded three songs with them, including "Nonetheless in Love with Yous", which he co-wrote. The song was later included on Thin Lizzy's fourth album Nightlife. Moore then left Thin Lizzy in Apr 1974.[xvi] While he enjoyed his time in the band, Moore felt it wasn't practiced for him, stating: "After a few months I was doing myself in, drinking and loftier on the whole thing."[3]

In 1977, Moore rejoined Thin Lizzy for a tour of the Us subsequently guitarist Brian Robertson injured his mitt in a bar fight.[17] Subsequently finishing the tour, Lynott asked Moore to bring together the ring on a permanent basis, but he declined.[xviii] Brian Robertson eventually returned to the grouping, earlier leaving for good in 1978. Moore took his place once over again, this fourth dimension for long enough to record the anthology Blackness Rose: A Stone Fable, which was released in 1979. The tape was a success, existence certified gilt in the Uk.[xix] Still, Moore abruptly left Thin Lizzy that July in the middle of another tour. He had get fed upwards with the band's increasing drug use and the effects information technology was having on their performance.[20] Moore afterward said he had no regrets nearly leaving the band, "only mayhap it was incorrect the fashion I did it. I could've done it differently, I suppose. But I just had to leave."[21] Thin Lizzy would eventually disband in 1983 with Moore making invitee appearances on the band's farewell tour. Some of the performances were released on the live album Life.[22]

Following Lynott's decease in January 1986,[ii] Moore performed with members of Thin Lizzy at the Self Aid concert the following May.[23] He joined the phase with former Thin Lizzy members again in August 2005, when a bronze statue of Lynott was unveiled in Dublin. A recording of the concert was released as Ane Night in Dublin: A Tribute to Phil Lynott.[24]

Solo career [edit]

In 1973, Moore released the anthology Grinding Stone, which was credited to The Gary Moore Band.[13] [25] An eclectic mix of blues, rock and jazz,[26] the album proved to be a commercial flop with Moore still unsure of his musical direction.[13] [27] [28] While yet a fellow member of Thin Lizzy, Moore released his start proper solo album Back on the Streets in 1978.[25] [29] Information technology spawned the hit single "Parisienne Walkways", which too featured Phil Lynott on atomic number 82 vocals and bass. The song reached number eight on the UK Singles Nautical chart and is considered Moore'southward signature song.[25] Later leaving Thin Lizzy in 1979, Moore relocated to Los Angeles where he signed a new recording contract with Jet Records.[thirty] He recorded the album Dingy Fingers, which was shelved in favour of the more "radio-oriented" Chiliad-Force album, which came out in 1980. Muddied Fingers was eventually released in Nippon in 1983, followed by an international release the next year.[31] [32]

Moore performing at the Manchester Apollo in 1983.

After moving to London and signing a new recording contract with Virgin, Moore released his second solo album Corridors of Ability in 1982.[30] While not a major success, it was the first album to feature Moore on lead vocals throughout,[xxx] also as his commencement solo release to crack the Billboard 200 chart.[33] Musically Corridors of Ability featured "more of a stone experience",[14] with additional influences from AOR bands, such as Journey and REO Speedwagon.[30] The anthology likewise featured sometime Deep Purple drummer Ian Paice, Whitesnake bassist Neil Murray, and keyboardist Tommy Eyre, who had previously played with Moore in Greg Lake's backing ring. During the supporting tour for Corridors of Power, singer John Sloman was also hired to share lead vocal duties with Moore, while Eyre was replaced by Don Airey.[13] [34] In 1983, Moore released the anthology Victims of the Future, which marked some other musical modify, this time towards hard rock and heavy metal.[14] The album likewise saw the add-on of keyboardist Neil Carter, who would keep to push Moore in this new musical direction.[13] For the supporting tour, they were joined by one-time Rainbow bassist Craig Gruber and drummer Bobby Chouinard,[35] [36] who were afterwards replaced by Ozzy Osbourne bassist Bob Daisley and former Roxy Music drummer Paul Thompson, respectively.[37]

In 1985, Moore released his fifth solo anthology Run for Comprehend, which featured guest vocals by Phil Lynott and Glenn Hughes.[38] Moore and Lynott performed the hitting single "Out in the Fields", which reached the summit 5 in both Ireland and the UK.[39] [40] On the back of its success, Run for Comprehend achieved gold certification in Sweden, too every bit silverish in the UK.[41] [42] For the album'south supporting tour, Paul Thompson was replaced by drummer Gary Ferguson. Glenn Hughes was supposed to join the band on bass, but due to his substance abuse problems, he was replaced by Bob Daisley.[43] [44] Following Phil Lynott's death, Moore dedicated his 6th solo album, 1987's Wild Frontier, to him.[thirteen] A blend Celtic folk music, dejection and rock,[30] the album proved to be another success, being certified platinum in Sweden,[41] gilded in Finland and Kingdom of norway,[45] [46] as well as silvery in the United kingdom.[47] The anthology also spawned the hit single "Over the Hills and Far Away", which charted in nine countries. For the accompanying bout, former Black Sabbath drummer Eric Singer joined Moore's bankroll band.[48] Wild Frontier was followed up by 1989's After the War, which featured drummer Cozy Powell. However, he was replaced by Chris Slade for the supporting tour.[49] [l] While Afterwards the War achieved gold status in Deutschland and Sweden,[41] [51] as well as silver in the Britain,[52] Moore had grown tired of his own music. Moore told former Thin Lizzy guitarist Eric Bell that afterward listening to some of his own albums, he thought they were "the biggest load of fucking shite" he had ever heard. In his own words, Moore had lost his "musical cocky‑respect".[30]

Moore performing in 2010.

In 1990, Moore released the album Nonetheless Got the Blues, which saw him returning to his blues roots and collaborating with the likes of Albert Rex, Albert Collins and George Harrison.[30] The idea for the record had come up during the supporting tour for After the War – Moore would often play the dejection by himself in the dressing room when one night Bob Daisley jokingly suggested that he do a whole blues album.[5] [50] This modify in musical fashion was also underlined by a alter in Moore's wardrobe. He now sported a smart blue suit for videos and live performances instead of being "all dolled upwardly like some guy in Def Leppard". This was a conscious determination by Moore to attract new listeners and inform his quondam audience that "this was something new".[30] In the finish, Still Got the Blues proved to be the most successful anthology of Moore's career,[30] selling over three million copies worldwide.[l] The album'due south title track besides became the only single of Moore'south solo career to chart on the Billboard Hot 100, where it reached number 97 in February 1991.[53] For the album'south supporting bout, Moore assembled a new backing band, dubbed The Midnight Blues Band, featuring Andy Pyle, Graham Walker, Don Airey, as well as a horn section.[50]

Still Got the Dejection was followed upwardly by 1992's After Hours, which went platinum in Sweden and gold in the UK.[41] [54] The record also became Moore'due south highest charting album in the U.k. where it reached number four.[55] In 1995, Moore released Dejection for Greeny, a tribute album to his friend and mentor Peter Green.[56] After experimenting with electronic music on Dark Days in Paradise (1997) and A Different Beat (1999), Moore once again returned to his blues roots with 2001's Back to the Blues.[11] [57] This was followed-upwards by Ability of the Dejection (2004), Old New Ballads Blues (2006), Close as Y'all Get (2007), and finally Bad for You Baby (2008).[58] Prior to his death, Moore was working on a new Celtic stone album that was left unfinished. Some of the songs would later appear on the live album Live at Montreux 2010.[59] Additional unreleased recordings of Moore'south were released on the album How Blue Can You Get in 2021.[lx]

Other work [edit]

In 1975, Moore joined progressive jazz fusion group Colosseum 2, which was formed after the demise of bandleader Jon Hiseman's previous band Colosseum. Moore recorded iii albums with the group, earlier leaving to bring together Thin Lizzy in 1978.[fourteen] [61] While living in Los Angeles in 1979, Moore formed the ring One thousand-Strength with Glenn Hughes and Mark Nauseef.[30] [62] All the same, Hughes was soon replaced by Willie Dee and Tony Newton due to his drinking problem.[63] [64] At the same time, Moore was too beingness courted to bring together Ozzy Osbourne'south band. He declined, simply G-Force helped Osbourne audition other musicians for his band.[30] [57] G-Force later released their cocky-titled debut album in 1980, and toured opening for Whitesnake. Before the terminate of the year, still, the band bankrupt up.[62] [64] Moore was and so recruited to play guitar in Greg Lake'due south solo band. They recorded two studio albums together, 1981's Greg Lake and 1983's Manoeuvres,[fourteen] every bit well every bit the alive album King Biscuit Flower 60 minutes Presents Greg Lake in Concert, which was released in 1995.[65] In 1982, Moore was considered for the guitarist position in Whitesnake, but vocalist David Coverdale opted not to recruit Moore as the band were in the process of severing ties with their direction.[66] In 1987, Moore collaborated on the U.k. charity tape "Permit Information technology Exist", which was released nether the group name Ferry Assistance.[58]

From 1993 to 1994, Moore was a member of the brusk-lived ability trio BBM ("Baker Bruce Moore"), which also featured Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker, both formerly of Cream. Subsequently merely one album and a European tour, the trio disbanded. The projection was marred by personality clashes between members equally well as "ear issues" Moore sustained during the tour.[67] Moore later said of the ring'southward break-up: "There were a lot of things within the band that would take made information technology incommunicable, long term. I think that politically Jack [Bruce] was used to having his ain band, I was used to having my ain band and then it was very difficult."[56] In 2002, Moore collaborated with one-time Skunk Anansie bassist Cass Lewis and Key Scream drummer Darrin Mooney in Scars, which released one album.[68] Moore also performed on the I World Projection charity unmarried "Grief Never Grows Old", which was released in 2005.[69]

Over the course of his career, Moore played with several of other artists, including George Harrison,[70] Dr. Strangely Strange,[71] Andrew Lloyd Webber, Rod Argent, Gary Boyle,[61] B.B. Rex,[72] The Traveling Wilburys and The Beach Boys.[73]

Personal life [edit]

In the mid-1970s, Moore was involved in a bar fight which left him with facial scars. According to Eric Bell, Moore was with his girlfriend at Dingwalls when two men "started mouthing almost Gary's girlfriend [...] what they'd like to practise to her". After Moore confronted them almost it, one of the men smashed a bottle on the bar and slashed his face up with it. This had a profound effect on him. Bell said, "It did modify him. A lot of that pent-up anger and emotion would come up out in his playing. And information technology came out in other ways too. It must be a hard thing to come dorsum from something like that." During the 1980s, he would hide his scars in photographs and videos by looking down or beingness framed from a distance.[thirty] [74]

Moore was married to his first wife Kerry from 1985 to 1993.[50] [75] [76] They had two sons, Jack (who would also become on to become a musician[77]) and Gus, before divorcing.[75] Moore subsequently had a daughter, Lily (who besides embarked on a career in music[78]), during a relationship with Jo Rendle.[75] [79] Moore as well had a daughter named Saoirse from another relationship.[80] At the fourth dimension of his expiry, Moore was in a relationship.[81]

Expiry [edit]

During the early hours of 6 February 2011, Moore died of a heart attack in his sleep at the age of 58. At the time, he was on holiday with his girlfriend at the Kempinski Hotel in Estepona. His death was confirmed past Thin Lizzy's manager Adam Parsons.[81] [82] [83] The Daily Telegraph reported that his center attack was brought on by a high level of alcohol in his torso: 380 mg of alcohol per 100 ml of claret.[81] Co-ordinate to music announcer Mick Wall, Moore had developed a serious drinking problem during the last years of his life.[64]

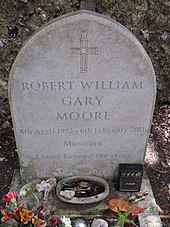

Moore was cached in a private anniversary at St Margaret'south Churchyard in Rottingdean on the south coast of England, with only family unit and close friends in attendance. His eldest son Jack and his uncle Cliff performed the Irish ballad "Danny Boy" at his funeral. This was reported in The Belfast Telegraph every bit "a flawless tribute at which some mourners in the church wept openly".[84]

Style and influences [edit]

Moore was known for having an eclectic career, having performed blues, difficult rock, heavy metal and jazz fusion.[39] [83] At times he was accused of chasing trends, which Moore denied, stating that he'd always merely washed what he liked at the time.[57] Following Still Got the Blues, Moore distanced himself from his 1980s difficult rock image. While he still enjoyed stone music in general, he no longer identified himself every bit a rock guitarist, stating: "I'm not that guy anymore, to be honest with you. If I go back and mind to some of that stuff, I become, 'Shit. Did I really play that?' Information technology just sounds quite alien to me in some ways. – Information technology's just not the way I desire to play."[85] Many of Moore'south songs were autobiographical or they dealt with topics important to him.[86]

Moore was known for his pained expressions during live performances.

1 of Moore'south biggest influences was guitarist Peter Green. The first time Moore heard Green play was at a performance with John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers, of which he said: "It was an amazing experience merely to hear a guitarist walk on stage and plug into this amplifier, which I thought was a pile of shit, and go this incredible sound. He was admittedly fantastic, everything about him was so graceful."[56] Moore eventually met Green in January 1970 when Slip Row toured with Green'southward band Fleetwood Mac.[50] The two became friends and Green later sold his 1959 Gibson Les Paul to Moore.[87] [88] Some other major influence of Moore'southward was Eric Clapton, whom he first heard on the John Mayall & The Bluesbreakers album Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton. Moore later on described this equally a life-changing experience: "Within two seconds of the opening track, I was blown abroad. The guitar sound itself was and then dissimilar. Y'all could hear the blues in it, but prior to that all the guitar you heard in rock, well pop, music had been very staid, very polite. Only mind to the early Beatles and The Shadows to run across what I mean. They were cracking, but Eric Clapton transcended it completely."[89] Some of Moore'southward other early influences included Jeff Beck, George Harrison, Jimi Hendrix, Hank Marvin, John Mayall, and Mick Taylor.[13] [85] [86] He also cited Albert Male monarch and B.B. Male monarch equally influences.[86]

Moore has been described equally a virtuoso by numerous publications.[4] [5] [25] [58] Don Airey described him every bit a genius, while guitarist Bernie Marsden stated that "Gary could play literally any style".[64] Moore was known for his melodic sensibilities, as well as his ambitious vibrato. During the 1980s, he oft used major or natural minor scales. During the 2nd half of his career, Moore's playing was characterised by his use of pentatonic and dejection scales.[90] For more melodic leads, Moore would oftentimes use the guitar'due south neck pickup, while the span pickup was used to attain a more than aggressive sound.[91] Regarding his style of playing, Moore said the best piece of advice he e'er received came from Albert King, who taught him the value of leaving space. Moore stated: "When you go into the habit of leaving a infinite, y'all become a much better histrion for it. If you've got an expressive manner and can express your emotions through your guitar, and you've got a peachy tone, it creates a lot of tension for the audience. Information technology's all down to the feel affair. If yous've got a feel for the blues, that's a large part of it. But yous've got to get out that space."[5] Moore was also known for having pained expressions while performing, something he said was not a witting activity. When asked almost information technology, he stated: "When I'm playing I get completely lost in information technology and I'm non fifty-fifty enlightened of what I'm doing with my face — I'thou just playing."[76]

Moore was often described equally "grumpy" and he had a reputation of existence hard to work with.[v] [xiv] [30] Brian Downey described him equally "cranky" at times, while Eric Bong recalled a particular incident after a concert in Dublin: "I went to see him in the dressing room afterwards. — I sat down abreast him and said, 'Fucking not bad gig, Gary.' He looked at me. 'What? Fucking load of shite! I've never played so bad in my fucking life!' I saw that side of him quite a lot."[30] This was echoed by Downey, who stated that if a evidence wasn't perfect it would torment Moore.[64] While Moore acknowledged his reputation of being difficult to work with at times, he attributed this to his own perfectionism, belongings others up to the aforementioned standards he set for himself.[fourteen] Don Airey would later state that Moore'southward perfectionism was often to his ain detriment.[64]

Legacy [edit]

"I don't know. Nevertheless they desire! As somebody that didn't bullshit. Any I did, at least I meant it. That's all I can say really 'cos I normally practise mean it. I'm not full of shit like a lot of people. Whatsoever I do, whether it sells or not, at to the lowest degree I mean it at the time and I'm honest well-nigh information technology. Which I call back is the only way to exist."

—Gary Moore on how he'd like to be remembered.[76]

Post-obit his death, many of Moore's fellow musicians paid tribute to him, including his one-time Thin Lizzy bandmates Brian Downey,[92] and Scott Gorham,[83] as well as Bryan Adams,[93] Bob Geldof,[94] Kirk Hammett,[95] Tony Iommi,[96] Alex Lifeson,[97] Brian May,[98] Ozzy Osbourne,[99] Paul Rodgers,[100] Henry Rollins,[93] Roger Taylor,[101] Butch Walker,[93] and Mikael Åkerfeldt,[102] amongst many others. Thin Lizzy too defended the remainder of their ongoing tour to Moore.[92] Eric Clapton performed "Notwithstanding Got the Dejection" in concert as a tribute to Moore, and the song was later featured on Clapton's 2013 anthology Old Sock.[50] On 12 March 2011, a tribute night was held for Moore at Duff's Brooklyn in New York City.[103] On 18 Apr 2011, a number of musicians, including Eric Bell and Brian Downey, gathered for a tribute concert at Whelan'due south in Dublin.[104]

In 2012, an exhibition celebrating the life and work of Moore was held at the Oh Yeah Music Centre in Belfast.[105] To commemorate what would accept been his father's 65th altogether, Jack Moore along with guitarist Danny Immature released the tribute song "Phoenix" in 2017.[106] That same year, guitarist Henrik Freischlader released a tribute album to Moore, titled Dejection for Gary.[107] In 2018, Bob Daisley released the album Moore Blues for Gary – A Tribute to Gary Moore, which featured the likes of Glenn Hughes, Steve Lukather, Steve Morse, Joe Lynn Turner, Ricky Warwick, and many others.[108] On 12 April 2019, a tribute concert for Moore was held at The Belfast Empire Music Hall to aid raise funds for a memorial statue.[109] On 28 August 2020, Über Röck announced plans to host a tribute concert in Belfast on 6 February 2021 to mark the 10th ceremony of Moore's decease.[110]

Moore has been cited as an influence by many notable guitarists, including Doug Aldrich,[111] Joe Bonamassa,[112] Vivian Campbell,[113] Paul Gilbert,[114] Kirk Hammett,[115] John Petrucci,[116] John Sykes,[117] and Zakk Wylde.[118] In 2018, Moore was voted number xv on Louder's listing of "The fifty All-time Guitarists of All Time".[119] In 2020, he was placed on a list of "The 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time" past Full Guitar.[120] Classic Stone included him on their 2021 listing of "The 100 Most Influential Guitar Heroes".[64]

Equipment [edit]

Guitars [edit]

Gibson Gary Moore Signature Les Paul

The guitar most associated with Moore was a 1959 Gibson Les Paul, which was sold to him past Peter Green for around £100.[121] The guitar, nicknamed "Greeny", is known for its unusual tone, the upshot of a reversed cervix pickup. Moore used the guitar for most of his career (almost notably on "Parisienne Walkways"), until he sold it in 2006 for somewhere between $750,000 and $1.2 meg. The guitar was purchased past Metallica guitarist Kirk Hammett in 2014 for what was reportedly "less than $2 million".[122] On Still Got the Blues, Moore used some other 1959 Gibson Les Paul Standard, nicknamed "Stripe", which he bought in 1989.[86] [123] [124] Bated from a refret (Moore favoured jumbo frets) and new Grover tuners, the guitar was all stock.[124] The guitar was retained by Moore'southward manor following his expiry.[123] In 2000–2001, Gibson released a Gary Moore Signature Les Paul Standard with a faded lemonburst finish and a reversed neck pickup. Gibson later released a Gary Moore Signature BFG Les Paul, featuring a P-ninety pickup in the neck position.[125] In 2013, Gibson announced a new Gary Moore Signature Les Paul, modelled after the "Greeny" guitar.[126]

On Corridors of Power and Victims of the Futurity, Moore used a 1961 Fiesta Red Fender Stratocaster, which had previously belonged to Tommy Steele. In 2017, Fender Custom Shop released a limited edition replica of the guitar.[thirteen] [127] [128] During the 1980s, Moore also played Hamer and PRS guitars, equally well as Charvels equipped with Floyd Rose tremolos and EMG pickups.[xiii] Other guitars Moore used during his career include a 1964 Gibson ES-335, and a 1968 Fender Telecaster, amid many others.[13] [86] After his death, a number of Moore'due south guitars were auctioned off. These included a 1963 Fender Stratocaster given to him by Claude Nobs, a Fritz Brothers Roy Buchanan Bluesmaster, a 2011 Gibson Les Paul Standard VOS Collector's Choice No. 1 Artist's Proof No. 3 (modelled after the "Greeny" guitar), and a 1964 Gibson Firebird 1.[129]

Moore began playing with .009-.046 gauge strings, before switching to .010-.052. Later he switched to guess .009-.048.[86] Moore'south preferred brand of strings was Dean Markley. He also used actress-heavy picks.[124]

Other equipment [edit]

Moore used Marshall amplifiers during most of his career. He utilized other brands from time to time as well, including Dean Markley, Gallien-Krueger and Fender.[13] [130] [131] Some of the effects pedals Moore used during the 1980s included a Boss DS-1, an Ibanez ST-9 Super Tube Screamer, a Roland Space Echo, a Roland SDE 3000 Digital Delay and a Roland Dimension D.[13] [130] After he used a variety of effects past T-Rex, an Ibanez TS-10 Tube Screamer Classic and a Marshall Guv'nor, the last of which was featured near notably on "Still Got the Blues".[86] [130] In the studio, Moore used an Alesis Midiverb II since the late 1980s.[86] Moore was too an early adopter of the pedalboard, namely the Dominate BCB-6 "Carrying Box", which he used in the early 1980s.[132]

Discography [edit]

Solo albums [edit]

- Back on the Streets (1978)

- Corridors of Power (1982)

- Muddy Fingers (1983)

- Victims of the Futurity (1983)

- Run for Cover (1985)

- Wild Frontier (1987)

- After the War (1989)

- Even so Got the Blues (1990)

- After Hours (1992)

- Dejection for Greeny (1995)

- Night Days in Paradise (1997)

- A Different Beat (1999)

- Back to the Dejection (2001)

- Power of the Blues (2004)

- Old New Ballads Dejection (2006)

- Close equally You Get (2007)

- Bad for Y'all Baby (2008)

- How Blue Tin can Y'all Get (2021)

References [edit]

- ^ "Gary Moore: an obituary". BBC News. 7 February 2011. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d east "Moore'due south almanac". Belfast Telegraph. ii May 2007. Archived from the original on xiv August 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sweeting, Adam (seven Feb 2011). "Gary Moore obituary". The Guardian . Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ a b c Perrone, Pierre (2 March 2011). "Thin Lizzy's Gary Moore in aboveboard BBC One documentary". BBC. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d eastward f yard Perrone, Pierre (viii February 2011). "Gary Moore: Virtuoso guitarist who had his biggest hits with Phil Lynott and Sparse Lizzy". Contained. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ Moseley, Willie G. "Gary Moore – Back to the Stone". Independent. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ Trivial, Ivan (14 February 2011). "Is this y'all pictured with thirteen-yr-old Gary Moore?". Belfast Telegraph . Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ "Gary Moore remembers Rory Gallagher". Hot Press. 11 June 2015. Retrieved ane September 2020.

- ^ Thomson 2016, p. 56.

- ^ Putterford 1994, pp. 33–35.

- ^ a b c "Biography". Gary Moore – The Official Spider web Site. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Slip Row (seventy's)". Official Charts. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d due east f g h i j k l "Gary Moore Discusses His Latest Album, Gear and Phil Lynott in 1987 Guitar World Interview". Guitar World. 1 September 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g "On this day in 1952: Thin Lizzy guitarist Gary Moore was born". Hot Printing. 4 April 2019. Retrieved vii July 2020.

- ^ "Sebastian Bach Comments On 'SuperGroup' Flavour Finale". Blabbermouth.net. 3 July 2006. Archived from the original on 13 February 2011. Retrieved seven July 2020.

- ^ Putterford 1994, p. 89.

- ^ Black, Johnny (3 August 2017). "What happened the nighttime Brian Robertson got glassed at The Speakeasy". Louder. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ Putterford 1994, p. 133.

- ^ "BPI Awards Database: Search for Thin Lizzy". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Sparse Lizzy". Behind the Music. Season 3. Episode eleven. 17 October 1999. VH1.

- ^ Putterford 1994, p. 184.

- ^ Prato, Greg. "Thin Lizzy – Life". AllMusic. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- ^ Kavanagh, Jordan (1 May 2016). "30 years agone Republic of ireland was rocking out for the unemployed". TheJournal.ie. Retrieved vii July 2020.

- ^ "Gary Moore & Friends – Ane Dark in Dublin – A Tribute to Phil Lynott". AllMusic. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d Buskin, Richard. "Gary Moore 'Parisienne Walkways'". Sound On Sound. Retrieved vii July 2020.

- ^ Parker, Matthew (7 Feb 2011). "11 of the best Gary Moore performances". MusicRadar. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ Lovén, Lars. "Gary Moore Band / Gary Moore – Grinding Stone". AllMusic. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ Fielder, Hugh (4 November 2017). "The Gary Moore Band – Grinding Stone album review". Louder. Retrieved 31 Baronial 2020.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Gary Moore – Back on the Streets". AllMusic. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d due east f chiliad h i j k l m north "How The Dejection Saved Gary Moore". Louder. 1 September 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Gary Moore – Dirty Fingers". AllMusic. Retrieved vii July 2020.

- ^ Ling, Dave (2002). Dingy Fingers (booklet). Gary Moore. Sanctuary Records. 06076 81193-2.

- ^ "Billboard 200 – Week of June 4, 1983". Billboard Charts. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "John Sloman – Interview Exclusive". Über Röck. 24 August 2010. Retrieved 31 Baronial 2020.

- ^ "Original Rainbow Bassist Craig Gruber Dies After Battle With Prostate Cancer". Blabbermouth.cyberspace. six May 2016. Retrieved 1 Oct 2020.

- ^ Saccone, Teri. "Bobby Chouinard". Mod Drummer. Retrieved 1 Oct 2020.

- ^ Phil Tuckett (Director) (1985). Emerald Aisles: Live In Ireland (Concert film). Virgin Video.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Gary Moore – Run for Cover". AllMusic. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ a b Rivadavia, Eduardo (4 April 2013). "Top 10 Gary Moore Songs". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved seven July 2020.

- ^ "Out in the Fields". Official Charts. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d "IFPI Sweden – Gilt & Platinum 1987–1998" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 Feb 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Gary Moore – Run for Cover". BPI – British Phonographic Manufacture. Retrieved seven July 2020.

- ^ "Reggie talking with Gary Ferguson about Luke and many more than..." Steve Lukather Official Website. xiii May 2018. Retrieved 1 Oct 2020.

- ^ Fanelli, Damian (8 March 2012). "Interview: Glenn Hughes Discusses Deep Royal, Gary Moore, Beak Nash Basses and Writing with Black Country Communion". Guitar World. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ "Gary Moore – Kulta- ja platinalevyt". Musiikkituottajat. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Gold & Platinum Awards 1987" (PDF). American Radio History Archive. 2 Dec 1987. p. 44. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Gary Moore – Wild Frontier". BPI – British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Eric Vocalist: Gary Moore 'Played Every Note Like It Was The Last Fourth dimension He Would Ever Play Information technology'". Blabbermouth.cyberspace. 9 February 2011. Retrieved 1 Oct 2020.

- ^ "Gary Moore". The Neil Carter Homepage. Retrieved ii October 2020.

- ^ a b c d eastward f g Shapiro, Harry (i August 2016). "Gary Moore: the story of Still Got The Dejection". Louder. Retrieved seven July 2020.

- ^ "Gold-/Platin-datenbank – Gary Moore". Bundesverband Musikindustrie. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Gary Moore – Afterwards the War". BPI – British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Hot 100 – Calendar week of February xvi, 1991". Billboard Charts. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Gary Moore – After Hours". BPI – British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved vii July 2020.

- ^ "After Hours". Official Charts. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ a b c Mead, David (2 December 2019). "Classic interview: Gary Moore talks Blues For Greeny, Jack Bruce, Albert Collins and never playing with Clapton". MusicRadar. Retrieved seven July 2020.

- ^ a b c Ling, Dave (3 May 2006). "Gimme (Gary) Moore". Louder. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ a b c McIlwaine, Eddie (8 February 2011). "Gary Moore: Sparse Lizzy guitar virtuoso who blazed a unique trail through rock and roll". Belfast Telegraph . Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Gary Moore'southward 'Alive At Montreux 2010' Due In September". Blabbermouth.net. ii August 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ Bienstock, Richard (19 February 2021). "New Gary Moore album, How Blue Tin can You Get, to characteristic unreleased deep cuts and alternate versions". Guitar World. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ^ a b Prato, Greg. "Gary Moore – Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ a b Lovén, Lars. "Gary Moore / Gary Moore & G-Forcefulness – G-Force". AllMusic. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Glenn Hughes Remembers Gary Moore". Blabbermouth.net. 10 March 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f yard Wall, Mick (May 2021). "The 100 Most Influential Guitar Heroes: Gary Moore". Classic Stone. No. 287. London, England: Future Publishing. pp. 52–56.

- ^ Planer, Lindsay. "Greg Lake – Male monarch Beige Flower Hour: Greg Lake In Concert". AllMusic. Retrieved 24 Baronial 2020.

- ^ O'Neill, Eamon. "David Coverdale Whitesnake Eonmusic Interview October 2020 Function 2". Eonmusic. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ Shapiro, Harry (9 July 2018). "Ego, tempers, affairs: The tumultuous story of BBM". Louder. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ Donohue, Simon (i Feb 2007). "Gary just loves his scars". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Gary Moore Performs On One World Project Tsunami Clemency Single". BraveWords. i Feb 2005. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ Fanelli, Damian (1 September 2017). "George Harrison and Gary Moore Play "While My Guitar Gently Weeps" in 1992". Guitar World. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Moore ability". The Irish Times. 23 February 2001. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ Graham, Jonathan (half dozen Feb 2018). "Forgotten Guitar: B.B. Rex and Gary Moore Play "The Thrill Is Gone" in 1992". Guitar Earth. Retrieved seven July 2020.

- ^ Williams, Mackenzie. "Gary Moore, Legendary Axeman for Thin Lizzy, Has Died". BBC America. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Gary Moore – Belfast Boy and baby-faced dreamer". Belfast Telegraph. 8 February 2011. Retrieved 24 Baronial 2020.

- ^ a b c "Master Gary waiting for return telephone call to Belfast". Belfast Telegraph. 5 July 2005. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ a b c "Gary Moore: When I'yard playing I get totally lost in it". Belfast Telegraph. 8 Feb 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ McGreevy, Alex (eighteen September 2020). "Jack Moore: I would love to visit Belfast and see a statue celebrating my begetter and his music". Slabber.net . Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ Mahanty, Shannon (one December 2019). "Ane to watch: Lily Moore". The Guardian . Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ "Rock legend Gary Moore left manor of more than than £2m". Belfast Telegraph. iv April 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ Sweeney, Ken (24 February 2011). "Legendary guitarist Gary Moore laid to residual in moving anniversary". Independent.ie. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ a b c "Former Sparse Lizzy guitarist Gary Moore was v times drink drive limit when he died". The Daily Telegraph. 2 February 2012. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "One-time Sparse Lizzy guitarist Moore dies". The Irish Times. vi February 2011. Retrieved half dozen February 2011.

- ^ a b c "Gary Moore, Thin Lizzy guitarist, dies anile 58". BBC News. 6 February 2011. Retrieved 13 Baronial 2019.

- ^ "Sparse Lizzy guitar hero Gary Moore laid to rest as son plays Danny Boy". Belfast Telegraph. 2 February 2011. Retrieved seven July 2020.

- ^ a b The netherlands, Brian D. (1 July 2007). "Gary Moore Interview". The Sonic Blaze – The Site of Music Announcer Brian D. Kingdom of the netherlands. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f k h Sharken, Lisa. "Gary Moore: Nonetheless Got the Blues – Again!". Vintage Guitar Magazine. Retrieved vii July 2020.

- ^ Mead, David (2 June 2020). "How Gary Moore came to own Peter Greenish'southward iconic Les Paul, Greeny". Guitarist. Retrieved vii July 2020.

- ^ Leonard, Michael (2 March 2012). "Still Got the Blues: Gary Moore Remembered". Gibson. Retrieved vii July 2020.

- ^ Llewellyn, Sian (2 March 2007). "Gary Moore: "I jumped on the Blues bandwagon? I was the bandwagon!"". Louder. Retrieved one July 2020.

- ^ Cooper, Martin (7 February 2011). "How to play Gary Moore-fashion rock guitar". MusicRadar. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ Aledort, Andy (6 Feb 2020). "Principal the signature elements of Gary Moore'due south instantly identifiable guitar style". Guitar World. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ a b "Brian Downey Pays Tribute To Gary Moore". Planet Stone. 8 February 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ a b c Alexander, Bryan; Halperin, Shirley (half-dozen Feb 2011). "Gary Moore: Musicians Pay Tribute to Thin Lizzy Guitairist". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved seven July 2020.

- ^ "Bob Geldof pays tribute to Thin Lizzy'due south Gary Moore subsequently sudden hotel room death". The Telegraph. 7 February 2011. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Metallica's Kirk Hammett Remembers Gary Moore". Blabbermouth.net. 9 February 2011. Retrieved vii July 2020.

- ^ "Guns Due north' Roses, Black Sabbath Members Comment On Loss Of Gary Moore". BraveWords. vii Feb 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Blitz Guitarist Pays Tribute To Gary Moore". Blabbermouth.internet. 1 February 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Feb 2011". Brian'southward Discourse. 6 February 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Ozzy Osbourne On Gary Moore: 'Nosotros've Lost A Astounding Musician And A Great Friend'". Blabbermouth.net. 8 February 2011. Retrieved seven July 2020.

- ^ "Paul Rodgers Pays Tribute To Gary Moore". Blabbermouth.net. 8 Feb 2011. Retrieved seven July 2020.

- ^ "Queen's Roger Taylor On Gary Moore: 'His Music Volition Live On'". Blabbermouth.cyberspace. viii February 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Opeth's Mikael Åkerfeldt – "We Are Devastated To Hear About The Passing Of Gary Moore"". BraveWords. 6 February 2011. Retrieved seven July 2020.

- ^ "Gary Moore Tribute Night To Exist Held At Duff's Brooklyn". Blabbermouth.cyberspace. seven March 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Whelan's » Blog Archive » Gig for Gary". Whelanslive.com. i March 2011. Archived from the original on 16 April 2011. Retrieved v April 2011.

- ^ "Exhibition Celebrating Life And Piece of work Of Gary Moore Launched In Belfast". Blabbermouth.net. 4 Apr 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ Fanelli, Damian (ii April 2017). "Gary Moore's Son Plays His Father's Gibson Guitar in New Tribute Video". Guitar World. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ Fanelli, Damian (three March 2017). "Henrik Freischlader – Blues for Gary". Dejection Mag. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Gary Moore Tribute Album Due In October". Blabbermouth.net. two August 2018. Retrieved seven July 2020.

- ^ Colothan, Scott (ii January 2019). "Gary Moore tribute concert to raise funds for memorial statue". Planet Rock. Retrieved thirteen July 2020.

- ^ "Über Röck to host Gary Moore tenth anniversary celebration". Über Röck. 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Remainder in Peace Gary Moore". Dougaldrich.com. 1 February 2011. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved half dozen July 2011.

- ^ Bosso, Joe (three March 2010). "Joe Bonamassa: My xi favourite blues guitarists". MusicRadar. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Vivian Campbell: The Two Sides of If Interview". Guitar International. Archived from the original on 6 January 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Mr. Large Guitarist Paul Gilbert – "These Are The 10 Guitarists That Blew My Mind..."". BraveWords. 1 May 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ Greene, Andy (ix February 2011). "Metallica'southward Kirk Hammett Remembers Thin Lizzy's Gary Moore". Rolling Stone. Retrieved seven July 2020.

- ^ Bosso, Joe (3 November 2021). "John Petrucci: "When you lot solo, y'all're the vocalizer in the band... In that way, I've always been influenced past guys similar David Gilmour, Neal Schon and Gary Moore"". Guitar Earth. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ "Bad Boys Running Wild: Interview with John Sykes". Johnsykes.com. Archived from the original on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ Bosso, Joe (one August 2007). "The Man, The Myth, The Metal: Gibson Interviews Zakk Wylde". Gibson Lifestyle. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "The 50 Best Guitarists Of All Time 20–xi". Louder. 2 September 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ "The 100 greatest guitarists of all time". Total Guitar. 8 July 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ Mead, David (29 June 2020). "How Gary Moore came to own Peter Dark-green's iconic Les Paul, Greeny". Guitar World . Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ Scapelliti, Christopher (2 April 2017). "Kirk Hammett: "Jimmy Page Told Me to Buy Peter Green's Les Paul"". Guitar Globe. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ a b "Gary Moore's Guitars – plugging into history". YouTube. Guitarist. 1 January 2016. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ a b c Moon, Grant (1 July 2021). "How Gary Moore'due south propulsive playing and fiery tone inverse the course of blues guitar". Guitar Globe. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ Hunter, Dave (2 August 2018). "Legends of the Les Paul: Gary Moore". Gibson. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ Ability, Rob (2 April 2013). "Gibson announces Gary Moore Les Paul Standard". MusicRadar. Retrieved seven July 2020.

- ^ Dickson, Jamie (8 June 2017). "Under the microscope: Gary Moore'south Fiesta Red Fender Stratocaster". MusicRadar. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ Astley-Dark-brown, Michael (2 May 2017). "Fender Custom Shop unveils Gary Moore Stratocaster electrical guitar". MusicRadar. Retrieved seven July 2020.

- ^ Scapelliti, Christopher (five July 2016). "Gary Moore'south Guitars Fetch $190,000 at Sale". Guitar World. Retrieved seven July 2020.

- ^ a b c Marten, Neville (iii May 2016). "fourteen of Gary Moore's finest guitars, amps and furnishings – in pictures". MusicRadar. Retrieved vii July 2020.

- ^ Gill, Chris (ane November 2019). "The secrets behind Gary Moore'due south tone on However Got the Blues". Guitar World. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ Brakes, Rod (xxx November 2021). "Sentry Gary Moore in 1983 Introducing the Guitar World to the Pedalboard Concept". Guitar World. Retrieved 12 Dec 2021.

Sources [edit]

- Thomson, Graeme (2016). Cowboy Song: The Authorised Biography of Philip Lynott. Hachette U.k.. ISBN978-1-472-12106-6.

- Putterford, Mark (1994). Philip Lynott: The Rocker. Castle Communications. ISBN1-898141-50-9.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gary Moore. |

- Official website

- Gary Moore at IMDb

champagnebuth1999.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gary_Moore

0 Response to "It's Garry I Wanna Hit You to the Beat Its Garry Baby"

Postar um comentário